Smoking cannabis may help symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the short term, but can worsen the long-term prognosis.

This study states, “Medical marijuana: a panacea or tragedy?” For 5,000 years, cannabis has been “in medical, recreational and spiritual use around the world.” From the mid-19th century to the 1930s to the 1930s, it was stipulated “for numerous signs” by American physicians. This is a fact that advocates of medical marijuana are often used as evidence to justify modern medical applications. “However, the old-fashioned field of medicine is “full of potions and herb remedies.”

Skeptics criticize the medical marijuana movement as the “medical excuse” marijuana movement,” hoping that children with epilepsy and terminal illnesses will redirect “miracle cancer cures” to “scientists” who are either used as “trojan horses” for recreational cannabis use or who want to receive treatment for “miracle candidates” for miracle cancer.

For example, what about the therapeutic use of cannabis for inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis? Traditional treatments work primarily by suppressing the immune system and trying to reduce inflammation. Given the limited treatment options and known side effects of chronic use of these drugs, it is clear why people suffer from these diseases are so interested in alternative approaches, as people suffering from these diseases often need to surgically remove inflamed parts of their intestine.

Approximately one in six patients with IBD who use marijuana say it helps with symptoms, so researchers decided to go tested it. Thirteen patients with IBD were given a third of marijuana to smoke in their spare time for three months, and reported significantly better with “reporting reports of general health perceptions, social functioning, work ability, physical pain and depression.” There was no control group, so it is unclear whether the improvement was anyway and what role the placebo effect played. This is like some of the studies on cannabis used in childhood epilepsy have been reduced in frequency by 30% and in a third of children. The surprising result is that at my favorite Friday 2:21, I realized that I could get an equally amazing response from giving nothing but a sugar pill placebo, to being able to get an equally amazing response: cannabis for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Therefore, it is important to conduct a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, but it was not found in cannabis or IBD until 2013.

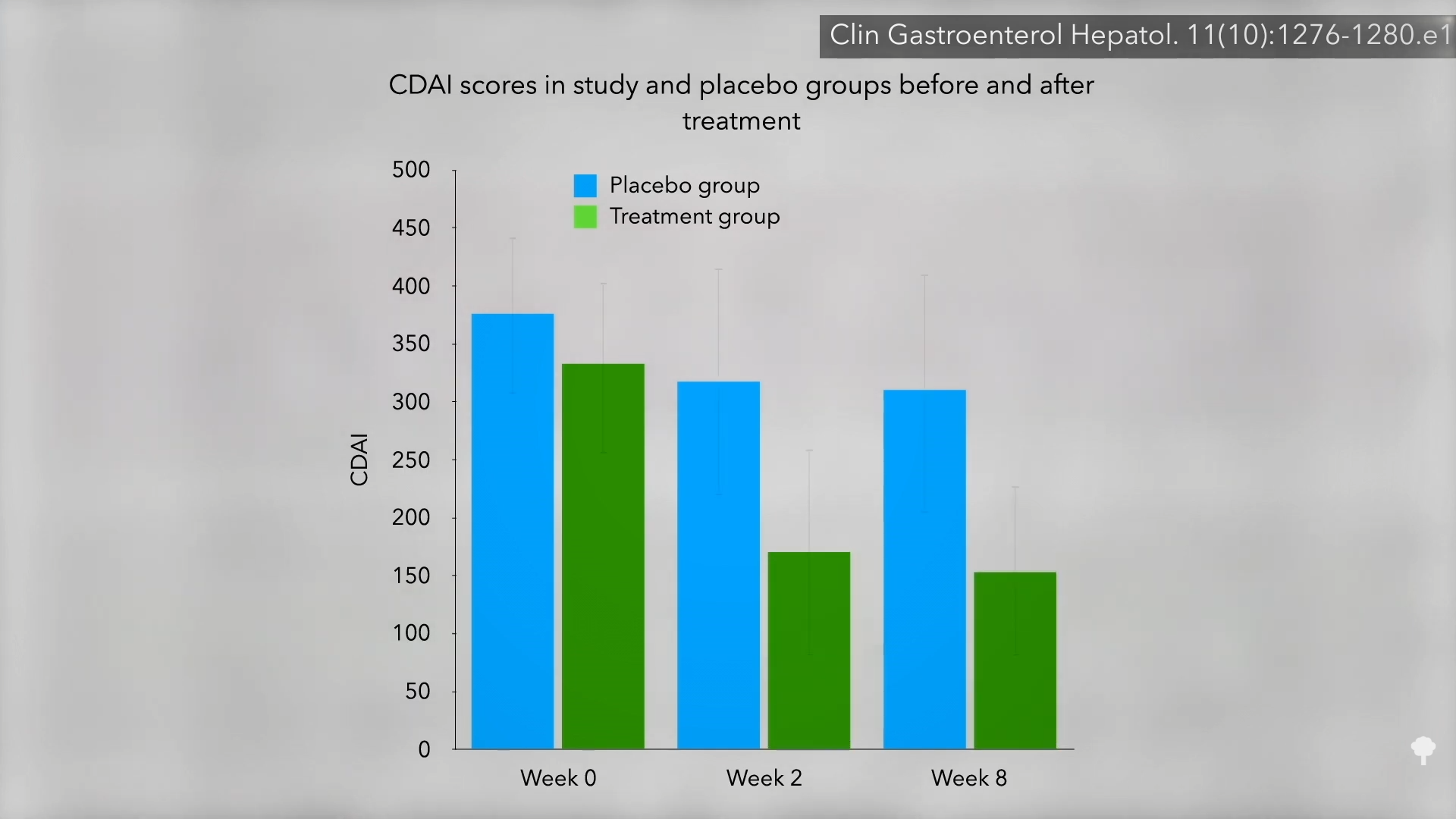

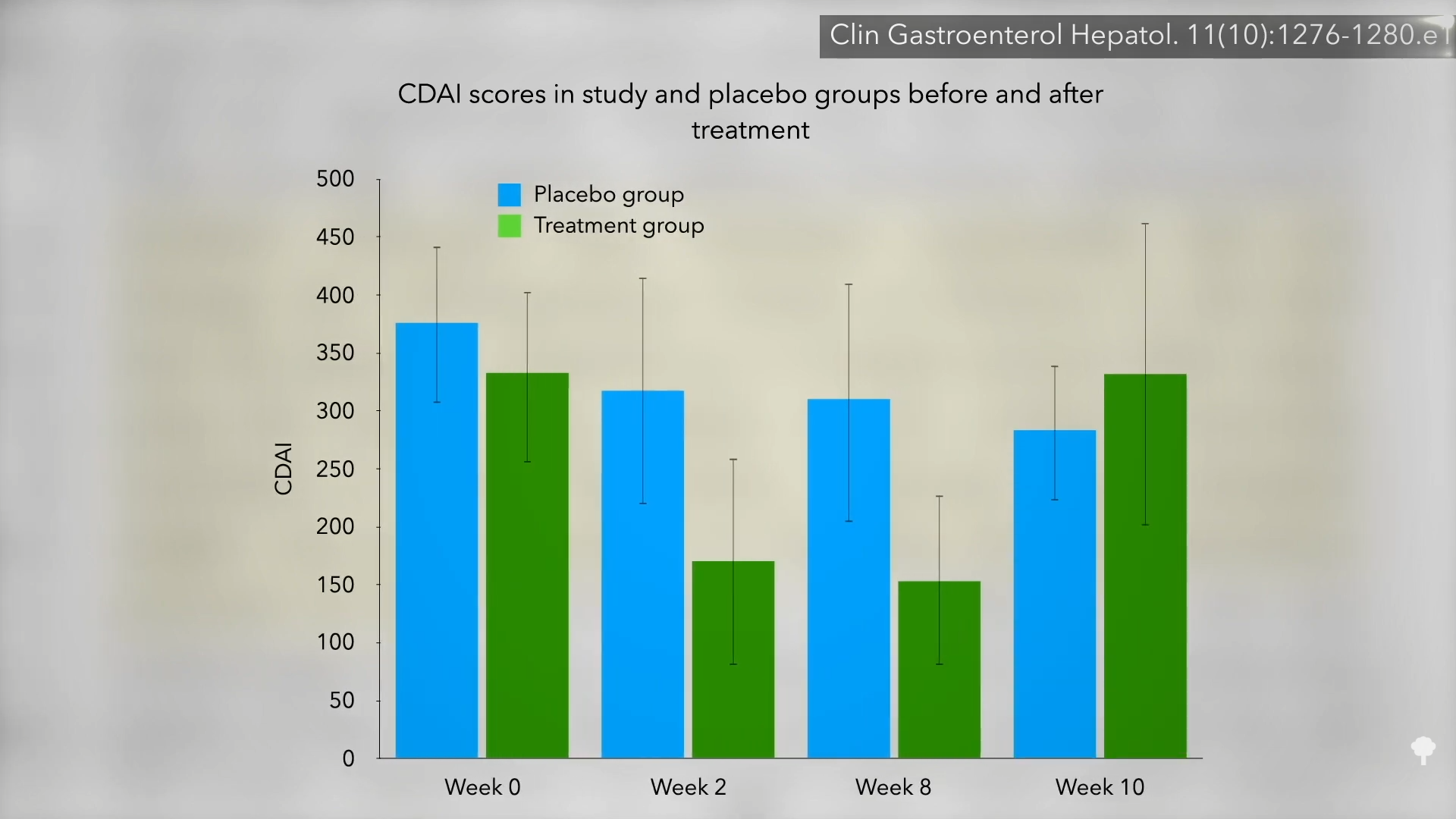

Nothing helped for 21 patients with Crohn’s disease. So the researchers randomized them to smoke two joints or a look placebo per day of marijuana. result? 90% of the cannabis group have improved compared to only 40% of the placebo group. At 3:11 in my video, I have a graph of the symptom scores. As you can see, there were no major changes in the placebo group in the two-month study, but the cannabis group reduced symptoms by about half.

Researchers acknowledge that long-term cannabis use is not without risks, but this study was told with “high hopes for medical marijuana in digestive disorders” because it could be a cakewalk compared to the effects beside the potentially unfavourable, and even life-threatening, traditional treatments.

This study was indeed funded by the country’s leading supplier, the medical marijuana advocacy organization. Therefore, participants may have been expected to be about how good they felt, that is, they may have been prepared for the placebo effect. But researchers managed it for that, right? Those who get real cannabis were significantly better than those who were randomised to get a placebo. But the key to a placebo is that it is indistinguishable from the real thing. Therefore, participants do not know which group they are in. It is a control group or treatment group. How can you achieve that with psychoactive drugs? That can’t be done, that’s the problem. The researchers tried to hide which group of participants were by recruiting only patients who had never tried cannabis before, hoping they would not notice the placebo pot, but of course most of them did. Therefore, there are basically other non-blended studies remaining. Researchers asked many subjective questions, such as “How are you?” And those who mostly knew they were taking medication said they were feeling better.

There was no significant change in objective lab values like CRP, a sign of inflammation, so perhaps “cannabis may just hide symptoms without affecting intestinal inflammation.” Another indicator that the disease itself may not be affecting the course of the disease itself is how quickly the symptoms rebound. Two weeks after the study was finished, the people in the cannabis group were quickly returning to where they started, as shown here at 5:05 in my video.

Therefore, “There was no difference in objective inflammatory markers to indicate disease modification. Given the rapid rebound, it appears that it is plausible that cannabis improved the symptoms of Crohn’s disease rather than actually modulating the disease until the pretreatment level after a two-week washout period.” That may be true, but the symptoms are terrible. Reducing pain is reduced pain. Certainly, “From a patient’s perspective, even if inflammation continues, the patient’s significant improvement and ability to resume normal life is not trivial.” Of course, what if cannabis could worsen the disease in some way in the long run?

A research study published the following year found that cannabis produced the same immediate symptomatic palliation, but was associated with a poor disease outcome over time. IBD patients reported that cannabis improved pain, convulsions and diarrhea, but was a strong predictor of clonal patients using it for more than six months and suffering from surgery. They were five times more likely to go under the knife. This has two explanations. It is very likely that an increased severity of the disease led to cannabis use, not the other way around. Another explanation: “Marijuana use can worsens the prognosis of IBD and can lead to greater surgeries and hospitalization.”

This is why we need a prospective clinical trial that people follow over time to see what comes first. Until then, IBD’s cannabis use should probably be considered “potentially harmful.” Not only is it careful, but there was a study in patients with hepatitis C who found that daily cannabis use was associated with almost seven times the worse odds of liver fibrosis like scar tissue. If cannabis actually exacerbates fibrosis, it may explain why cannabis users with IBD are more likely to need surgery.